Reuse of once unfashionable modernist buildings is increasingly favoured by developers, but one British city persists in demolition and rebuild, writes Joe Holyoak

Commercial property development is conventionally seen as a hard-headed and objective financial enterprise. It is measured in square metres, and calculated in pounds sterling. We speak of it in the developers’ language: development yield equals the net operating income divided by the total project cost. There is no room in it for subjective or sentimental elements which can’t be quantified.

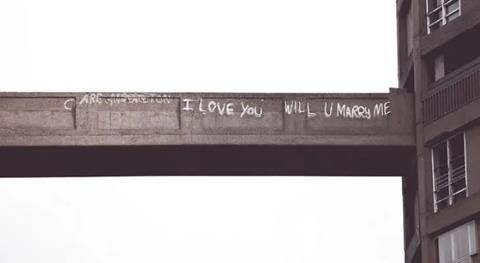

This isn’t true of course. At the recent Urban Design Group conference in Sheffield, Regeneration Director Mark Latham presented Urban Splash’s proposal for retrofitting Sheffield’s redundant John Lewis building. Urban Splash are as hard-headed and concerned with the bottom line as any developer, but they also have a sensitive ear for local history and human associations, and know the value that is embedded in these. The tale of the I LOVE YOU WILL U MARRY ME graffito on the bridge in Park Hill is a romantic one, but it is also a story of how a commercial developer spots an opportunity for adding an extra bit of appeal to the flats they are selling. I have the T-shirt.

John Lewis had a practice of acquiring local department stores, but enabling them to continue trading under their original names. This was a shrewd policy, which took advantage of the local reputation and goodwill which the original owner had accumulated over decades. In Sheffield, John Lewis acquired the store of Cole Brothers, which had been trading in Sheffield since 1847.

In 1963 it moved into a new building, an entire city block, designed by Yorke Rosenberg Mardall. It was a typical YRM building: severely rectangular, with gridded facades, on a concrete frame clad in white ceramic tiles – explicitly modernist. The business became a casualty of the economic decline, and the store closed in 2021. Urban Splash bought the redundant building.

At the conference, Mark Latham described how Cole Brothers was not only an established part of the city’s urban fabric, not only contained countless tons of embodied carbon, but was also firmly embedded in the personal histories and experiences of Sheffield’s citizens. It was a place where everybody had been shopping, met family, friends and lovers, and experienced both pleasure and sorrow.

The glib marketing slogan of retailers is that retail is not just shopping, but an experience. This is true, but it is only part of a wider and more complex truth about inhabiting the city.

Urban Splash recognised that people’s affection for the Cole Brothers’ institution extended to the container in which it was housed: despite its being an architecture that is commonly thought to be unpopular. Due to the efforts of the Twentieth Century Society, the building was listed at Grade II in 2022.

The retrofitted building will contain a mixture of uses. Urban Splash’s architects, AHMM, propose cutting an atrium out of the building in order to overcome the obstacle to re-use created by the deep retail floor plates, just as was done earlier by Urban Splash at Fort Dunlop, a deep warehouse planform.

To obtain as much commercial benefit as possible from the popular affection for the building, the new reincarnation will be named the Cole Store. Tom Hunt, Leader of the City Council, who introduced the conference, has earlier described the project as “an exciting plan for this landmark building”, and “an important part of the ongoing regeneration of our city centre”. His Strategy and Resources Committee voted positively for Urban Splash’s acquisition and transformation.

What a contrast with the fate of a landmark building in Birmingham that is a contemporary of YRM’s building, the Smallbrook Ringway Centre building designed by James Roberts, which I have written about here in an earlier column. Described by the Pevsner guide as “the best piece of mid-C20 urban design in the city”, the locally-listed building will be demolished and replaced by a banal highrise redevelopment designed by Corstorphine and Wright. The planning application was approved by seven votes to six at the Planning Committee on 28th September.

Those who voted for the redevelopment saw Roberts’ fine building not as an important element of the city’s heritage to be valued, but only as something to be casually swept away to allow progress to be made. The word “carbon” was not spoken once by any councillor. One councillor, who at least knew the word “retrofit”, asked why a retrofit alternative proposal had not been made: apparently unaware that the nationally- and locally-published alternative retrofit scheme had been sent to her personally.

Terms used by councillors to describe the Ringway Centre, which is one of the Twentieth Century Society’s 2023 top ten Buildings at Risk, included “architecturally ugly”, “historic only as old and outdated”, and “a concrete mess”. Sheffield, with an intelligent developer on board, makes a good decision and takes a big step forward.

Birmingham (whose civic motto, incidentally, is “Forward”), once more shoots itself in the foot.

Postscript

Joe Holyoak is an architect and urban designer practising in Birmingham

2 Readers' comments